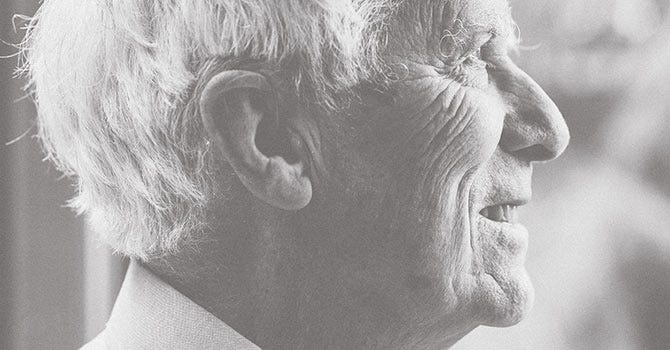

In his recent post on the Reformed Journal, philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff explores the implications of the recent synodical decisions of the Christian Reformed Church. He wonders what it means for those who, having grown up in the tradition, now find themselves to be outsiders—heretics is the word he uses. The problem for Wolterstorff isn’t just the decisions, but the lack of actual deliberation. There were forces at work that wanted to ensure the outcome. They weren’t there to discern the Spirit—they were there to get their way.

What’s fascinating about Dr. Wolterstorff’s piece are the comments. Most are supportive, while others express disappointment and disagreement. Never mind he is steeped in the Kuyperian tradition, a highly respected philosopher who carefully articulates his arguments. They’re upset because he doesn’t recognize the obvious—that synod merely confirmed what Christians have believed about sexuality and marriage for the last 2,000 years. To “reform”, from this perspective, is to get back to the way things were. That, according to these guardians of the faith, is where Dr. Wolterstorff is wrong.

After reading the comments, I found myself immersed in the writings of early Christians on the topic of marriage and sex. If what the guardians mean by a historical view of Christian marriage is that it has historically been the union of man and a woman, ok. What’s left unsaid, and unexplored, however, short circuits their case that to “reform” means to get back to something. The reformation is not a return to an early Christian view of marriage and sexuality; it’s something new. For early Christians, marriage was primarily about reproduction and sexual intercourse was a necessary evil. Here are some quotes to support this argument: (Quotes are taken from the book Marriage and Sexuality in Early Christianity by David G. Hunter, Editor.)

Tertullian: In sum, nowhere do we read that marriage is forbidden, since it is something good. But we have learned from the apostle what is better than this good, when he allowed marriage but preferred abstinence; the former because of the danger of temptation, the latter because of the end of time. If we examine the reasons given for each position, it is easy to see that the power to marry was granted to us out of necessity. But what necessity allows, it also depreciates. Scripture says: It is better to marry than to burn. What sort of good is it, I ask, that is commended only by comparison with an evil, so that the reason why marriage is better is because burning is worse? How much better it is neither to marry nor to burn!

Clement of Alexandria: In general, then, this is the question to be investigated: whether we should marry or completely abstain from marriage. In my work On Continence (Peri Enkrateias) I have already treated the subject. Now if we have to ask whether we may marry at all, how can we allow ourselves to make use of intercourse on every occasion, as if it were a necessity like food? It is clear that the nerves are stretched like threads and break under the tension of intercourse. Moreover, sexual relations spread a mist over the senses and drain the body of energy. This is obvious in the case of irrational animals and in persons undergoing physical training. Among athletes it is those who abstain from sex who defeat their opponents in the contests; as far as animals are concerned, they are easily captured when they are caught in and all but dragged away from the act of rutting, for all their strength and energy is completely drained.

The sophist of Abdera called sexual intercourse a “minor epilepsy” and considered it an incurable disease. Is it not accompanied by weakness following the great loss of seed? “For a human being is born of a human being and torn away from him.” See how much harm is done: a whole person is torn out with the ejaculation that occurs during intercourse. This is now bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh, Scripture says. By spilling his seed a man loses as much substance as one sees in a body, for what has been expelled is the beginning of a birth. Moreover, the shaking of the body’s material substance disturbs and upsets the harmony of the whole body. Wise, then, was the person who, when asked his opinion of the pleasures of love, replied: “Silence, man; I am very glad to have fled from them as from a fierce and raging tyrant.” Nevertheless, marriage should be accepted and given its proper place. Our Lord wanted humanity to multiply, but he did not say that people should engage in licentious behavior, nor did he intend for them to give themselves over to pleasure as if they were born for rutting.

Jerome: When you speak about virginity and continence, you say: It is good for a man not to touch a woman; and It is good for them to remain as they are; and I think this is good on account of the pressing distress; and It is good for a man to remain as he is. But when you come to marriage, you do not say, “It is good to marry,” because you cannot add the words “than to burn.” But you say: It is better to marry than to burn. If marriage is, in itself, good, do not compare it with burning, but simply say, “It is good to marry.” I am suspicious of the good of that thing which the greatness of another evil forces to be a lesser evil. But I do not want a lesser evil, but something that is simply good in itself.

Augustine: There is an additional good in marriage, namely the fact that carnal or youthful incontinence, even if it is wicked, is directed toward the honorable task of procreating children. As a result, conjugal inter- course makes something good out of the evil of lust (libido), since the concupiscence of the flesh, which parental affection moderates, is then suppressed and in a certain way burns more modestly. For a sort of dignity prevails over the fire of pleasure, when in the act of uniting as husband and wife the couple regard themelves as father and mother.

In all of these examples, marriage is a concession to human sin and the need for reproduction. Even for Augustine, who believes that marriage is grounded in the goodness of creation, the sex act must be brought under the control of reason, with a focus on reproduction, not pleasure. The libido for Augustine is lust; to enjoy sex is sinful. (This is in contrast to Lucius Caelius Firmianus Lactantius who maintained that God, “instilled in them the desire for each other along with delight in intercourse.”)

My purpose is not to disparage the views of early Christians, but to show that what happens at the reformation is radically different. For the reformers, the highest calling was not celibacy, and it was not the monastic life. Calvin especially wanted to bring the spiritual practices associated with the monastery into the home. (See the book Life in God: John Calvin, Practical Formation, and the Future of Protestant Theology.) Marriage was given a new status—it was reformed, which was much more than a return, it included something new. Yes, this something new was based on their reading of scripture, but so was the early Christian view of celibacy. It’s foolish to say Augustine, Clement, and others were not biblical, they simply came to different interpretations which informed their view of sex and marriage.

And let’s be honest—the early Christian views of sex and the body were at times problematic. What does it mean to engage in sex “rationally” so as not to experience pleasure? Very few Christians today—and I’m guessing very few of the decision makers at synod—view sex within marriage the way these early Christian did. Our understanding of human sexuality and marriage have changed.

Finally, I wonder if the guardians calling for a return to the early Christian view of marriage are going to make sure newlyweds don’t enjoy sex? I’ve been to a number of weddings in the Christian Reformed Church—receptions too. As we watch the bride and groom drive away on their wedding night, we’re all thinking the same thing: may they bring their sexuality under the control of reason, may they not enjoy one minute of this sinful—but necessary—act, and may they produce children as quickly as possible.

I have no problem if people disagree with Wolterstorff’s views of homosexuality and marriage. In fact, a few years back the Reformed Journal published a cordial, and thoughtful, discussion of the topic between Dr. Wolterstorff and Dr. Tuininga. But let’s give him the respect he is due. Of course he’s changed—it’s what it means to be a human being, walking the road to Mount Moriah, working out our faith with fear and trembling. And he knows a thing or two about what it means to be reformed, which is less about blindly following the way things have always been done, and learning to listen to the Word God speaks in Jesus Christ.